Let Justice Drip Like a Leaky Faucet

I gave this sermon at Claremont United Church of Christ on Sunday, January 14, 2024

I want to say, “Thank you” to both of your wonderful pastors, Jen and Jacob, for inviting me to speak as part of this series, “Airplane Mode,” in which we explore Richard Foster’s spiritual disciplines.

Last week, Pastor Jacob initiated this series with a teaching on the discipline of meditation. And this week, they asked me to speak with you about the spiritual discipline of service coupled with the life of Martin Luther King Jr.

So for all of my type-A friends who are here today,

I want to give you my outline for today’s sermon in advance

so you can relax for the rest of this sermon

because you will know that we have a plan for where we are going.

I’m going to start with three disclaimers,

then I am going to read from the book of Amos,

then I’ll share three stories from Dr. King’s life,

and then I’m going to end by asking you to think about

a leaky faucet multiple times.

Let’s begin with the disclaimers:

Disclaimer Number 1—This sermon is designed to start a discussion, not end one.

You’ll probably disagree with something I say in the next twenty minutes,

and that is more welcome.

Uniformity is not the reason I am here today.

Rather, the aim of this sermon is for my words

to spark a conversation in your life about what it means to be a more loving person.

Disclaimer Number 2—If we speak honestly about service today,

we have to begin with an acknowledgment that,

no matter how hard we try and how many hours we dedicate to serving another,

we will not be able to solve all of the world’s pain.

The author Anthony Doerr once wrote, “…to be a part of the problem is to be human.”

The great paradox of the Christian journey is that we are called to carry another’s pain

if we hope to do anything to help alleviate their pain.

This is what it means to become a compassionate person.

Disclaimer Number 3—In case you have not noticed yet, I am white…

which can be problematic when we are talking about the life and work of Martin Luther King Jr.

There is this idea amongst my progressive white siblings

that if Martin Luther King Jr. were alive today,

we would agree with everything he said and did.

But the truth is, MLK once wrote that the white middle-class moderates were,

“the Negro’s great stumbling block in the stride toward freedom,”

(Letter from a Birmingham Jail)

and even said he prefers members of the Klan to white moderates

because at least he knows where their allegiances lie.

I think it’s necessary for every white person in America today

to know these words before we start sharing opinions about Martin Luther King.

Because if we are unaware of his critique,

then we risk becoming the very person which he witnessed caused so much stumbling.

In all of my research of the life of Dr. King,

I have learned that what he believes America needs today

is not white people who say, “Well, I’m not a racist,”

but instead are willing to hold up a mirror and ask ourselves

“How am I part of the problem?”

And with those three disclaimers now declared,

we can now turn our attention to the book of Amos.

2700 years ago,

in the kingdom of Israel, there was a growing economic disparity

between the rich and the poor.

Landowners built extravagant estates at the expense

of poor farmers

further dividing people in this tiny nation into economic classes.

One of these farmers,

a man named Amos,

from the tiny village of Tekoa,

reached a boiling point.

He was fed up.

He was tired of seeing mansions being built with the money he earned.

He was angry that people were starving.

But the worst part of it all

for Amos

was the silence of the religious leaders

as this injustice unfolded in their back yard.

Rather than speaking in defense of the poor,

the religious leaders welcomed the economic disparity

by opening their arms to the generous tithes and offerings

the rich so freely gave to the religious system.

In his frustration,

Amos left his farm in Tekoa and traveled

to the royal sanctuary in Bethel.

When he arrived at the gates of the sacred architecture,

he made his feelings known with fire in his belly.

He wrote,

"(Thus says our God)

I despise and reject your feasts!

I am not appeased by your solemn assemblies!.

When you offer me burnt offerings,

I reject your oblations,

and refuse to look at your sacrifices of fattened cattle!

Spare me the racket of your chanting!

Relieve me of the strumming of your harps!

Instead,

let justice flow like a river,

and righteousness flow like an unfailing stream.”**

This is a line in the sand for Amos.

In the shadow of a sanctuary, he proclaims

the beauty of the temple is a waste,

the harmonies of the choir are pollution

the diligence of the verses recited are vanity

and the devotion of the prayers uttered are rubble

if the religious body leaves the poor to languish in poverty.

Instead, the work of God is one in which justice flows like a river

and righteousness flows like an unfailing stream

and the religious institution’s responsibility

is to stand up,

speak up,

and rise up

for the poor

and eliminate any and all distinctions

between who is rich and who is poor.

For Amos, the widening gap between

the rich and the poor

is the antithesis of the presence of God.

And religion’s responsibility is to act as a moral conscious for society

and defend and empower the poor whenever the rich gets too greedy.

Over 2500 years later,

on the other side of the globe and in a foreign land

the words and ideas of Amos

hit Martin Luther King Jr.

with a jolt of inspiration.

Even in the 20th century

these timeless words painted a bold vision for the future

and an unfettered proclamation for where God could lead America;

not only in matters of economic equality

but, for Dr. King, in matters of racial equality as well.

In the biggest speeches of his career

Martin Luther King returned to Amos’ words

time and time again

to show others a vision of what a decent and good society might be.

I want to share with you three stories when he employed the words of Amos for justice.

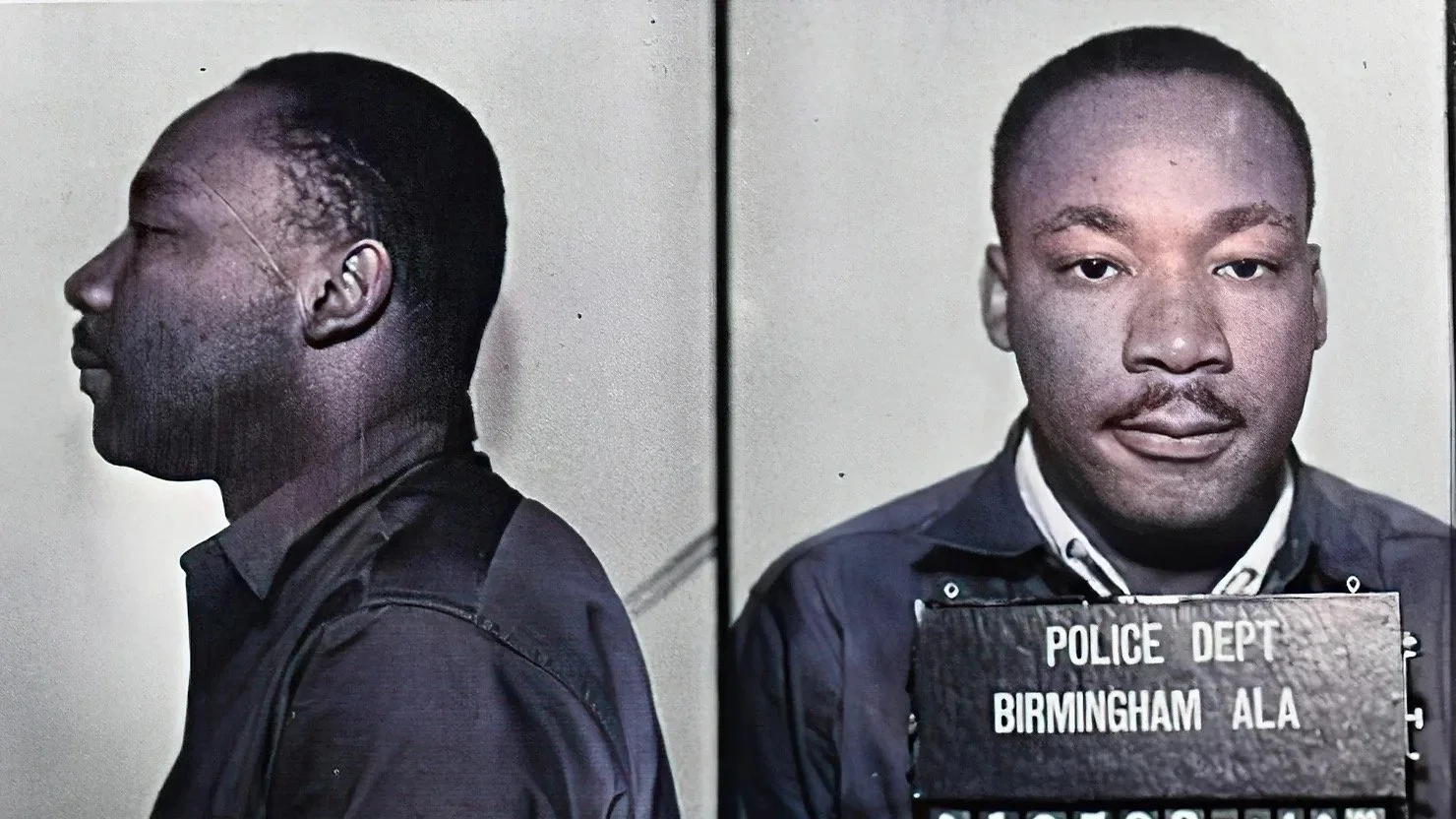

The first story unfolds in

1963 in Birmingham Alabama.

In his book, Why We Can’t Wait,

MLK refers to Birmingham, Alabama in 1963 as (SLIDE)

“the most segregated city in America.”

He recalled the story of when a federal court ordered

all public parks must be desegregated,

Birmingham chose to close all of its parks

rather than desegregate.

He pointed out that any person of African descent

was not welcomed at any white church in Birmingham.

Because even though these white Christians claimed Jesus as their Savior,

Dr. King said, they “practiced segregation as rigidly in the house of God

as they did in the theater.”

And he went on to remind the reader between 1957 and 1963,

seventeen bombings of black churches and homes of civil leaders occurred in Birmingham,

and all of them remained unsolved.

In order to bring attention to the injustice of segregation,

King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference protested in non-violent ways.

They disrupted society and commerce of the city of Birmingham

without once hurting another human being.

In retaliation, the city of Birmingham made it illegal to protest.

Which did not stop the good people of Birmingham from protesting.

They did not want the world to turn a blind eye to the sin of segregation.

And so they marched…

…and they were all arrested, including

Martin Luther King.

In his lifetime, this arrest was only one of over twenty times he was arrested.

While he was in jail, eight white Christian pastors from Birmingham wrote an open letter in the local paper entitled, “A Call for Unity.” In this letter, the eight pastors condemned King, and all of the leaders of Conference with him, for being outside agitators who were disrupting the peaceful city of Birmingham. While the pastors claimed they supported racial equality, they labeled King’s work as extreme.

In his jail cell, King pieced together scraps of paper and penned his “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” and forwarded it to the local paper. In this letter, he responded to the claim that his actions were extreme when he wrote,

“Was not Jesus an extremist in love? --

'Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, pray for them that despitefully use you.'

Was not Amos an extremist for justice when he wrote:

'Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.'

Was not Paul an extremist for the gospel of Jesus Christ? --

'I bear in my body the marks of the Lord Jesus.'

Was not Martin Luther an extremist?--

'Here I stand; I can do no other so help me God.'

Was not John Bunyan an extremist? --

'I will stay in jail to the end of my days before I make a mockery of my conscience.'

Was not Abraham Lincoln an extremist? --

'This nation cannot survive half slave and half free.'

Was not Thomas Jefferson an extremist? --

'We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.'

So the question is not whether we will be extremist,

but what kind of extremists we will be.

Will we be extremists for hate,

or will we be extremists for love?

Will we be extremists for the preservation of injustice,

or will we be extremists for the cause of justice?”

Just a few months later,

in Washington DC, Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin

organized a march on the nation’s capitol demanding

more jobs with higher pay for all people in America.

In response,

250,000 people made a pilgrimage to the city

and swarmed the Lincoln Memorial.

At this march, Martin Luther King stood up to speak

at the march on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

Today, what most white Americans forget

or are unaware of is that Dr. King’s work,

particularly toward the end of his life,

was as much an economic revolution

as it was a revolution for racial equality.

So here, in front of 250,000 people

and the history books of the United States of America,

Martin Luther King demanded racial and economic equality

with his most famous speech,

“I have a Dream”

which is far more aggressive than the carefully selected snippets we hear most often today.

He spoke these words:

“There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights,

'when will you be satisfied?'

We can never be satisfied

as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality.

We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies,

heavy with the fatigue of travel,

cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities.

We cannot be satisfied

as long as the Negro's basic mobility

is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one.

We can never be satisfied

as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood

and robbed of their dignity by signs stating: 'for whites only.'

We cannot be satisfied

as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote

and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote.

No, no,

we are not satisfied,

and we will not be satisfied

until justice rolls down like waters,

and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

A few months later, President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, prohibiting segregation and ensuring voting rights for all.

But white supremacists rebelled against this federal law.

In Selma, Alabama, these white supremacists

introduced racist hurdles for African-Americans

as they tried to exercise their right to vote.

To lament against this injustice,

600 nonviolent protestors began

a 54 mile march to Montgomery, the capitol of Alabama.

However, as soon as they crossed

the Edmund Pettis bridge at the edge of Selma,

state troopers unleashed horses, tear gas, and billy clubs

to break up the protest.

In front of cameras,

white police officers mercilessly beat American citizens.

Two days later, Martin Luther King arrived in Selma

to lead a second attempted march to Montgomery,

but stopped short when he sensed something was awry.

Twelve days later,

President Johnson and the federal government

offered military protection for the protestors

and on March 21, 1965

Dr. King led the march from Selma to Montgomery.

The protestors arrived in Montgomery on March 24,

and, the following day,

rallied on the steps of the capitol building

as they demanded uninhibited equal voting rights.

At this rally, Martin Luther King said,

“I know there is a cry today in Alabama,

we see it in numerous editorials:

'When will Martin Luther King…and all of these civil rights agitators…

get out of our community and let Alabama return to normalcy?'

But I have a message that I would like to leave with Alabama this evening.

That is exactly what we don’t want,

and we will not allow it to happen,

for we know that it was normalcy

in Marion that led to the brutal murder of Jimmy Lee Jackson.

It was normalcy

in Birmingham that led to the murder on Sunday morning

of four beautiful, unoffending, innocent girls.

It was normalcy

on Highway 80 that led state troopers

to use tear gas and horses and billy clubs

against unarmed human beings who were simply marching for justice.

It was normalcy by a cafe in Selma, Alabama,

that led to the brutal beating of Reverend James Reeb.

It is normalcy

all over our country which leaves the Negro perishing

on a lonely island of poverty

in the midst of vast ocean of material prosperity.

It is normalcy

all over Alabama that prevents

the Negro from becoming a registered voter.

No, we will not allow Alabama to return to normalcy.

The only normalcy that we will settle for

is the normalcy that recognizes the dignity and worth of all of God’s children.

The only normalcy that we will settle for

is the normalcy that allows judgment to run down like waters,

and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

In three of the most influential works of his career

Martin Luther King employed the words of Amos

demanding America pay attention to the injustices of her own cause

and to work toward a society of equality

in which “justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

This is no accident.

The prophet Amos is a kindred spirit of Martin Luther King.

While our society often thinks of a prophet

as someone who can accurately predict the future,

the prophets in the Bible, like Amos, are a different group of people entirely.

The best definition of a prophet I can give you is this:

A prophet is one who calls our attention to pain we wish to avoid

and asks us to do something about it.

By that definition, Amos was one of Israel’s greatest prophets

and Martin Luther King was America’s greatest prophet.

Rather than viewing Martin Luther King Jr as an American success story,

or the farmer Amos as a religious success story,

we should honor their legacies by asking,

“If these prophets were still alive,

what pain would they call our attention to today?”

And once we arrive at an answer,

the follow up is then, “And what would they ask us to do about it?”

A common thread between Amos and Dr. King

is their frustration toward the silence of the religious

in the face of injustice.

And this is something that we, as religious people, cannot forget in the year 2024.

While I believe it is good to be part of a religious body,

we must always be aware of the temptation we face:

the temptation of silence

for the sake of our convenience.

I recently came across a sign at a bar in Redlands which declared: (Slide)

“No sexism, racism, homophobia, or general hatefulness allowed.

You will be asked to Leave.”

Now this bar and this sign are far more inclusive and accepting

than most churches in my home town of Redlands.

But do you notice who is not welcome at this bar?

The poor.

The poor are not welcome in this establishment.

Because the poor do not have any value to most businesses.

And while I do not fault this bar for excluding the poor,

we must have higher standards for a church

which claims to be disciples of Jesus Christ.

As progressive churches,

we can be committed to the empowerment of women,

we can celebrate queer love

and affirm the image of God in all trans and non-binary persons,

and we can commit our lives to the sacred work of anti-racism,

but if we act like all of the other for-profit businesses in town

and do not find any value in those who are poor,

then, I must ask you,

what does our church sound like?

Drip

Drip

Drip

When I look at the life of Jesus

I am in awe of how he continually welcomed

people who society labeled as “sinners”

and affirmed the image of God in their life and in their experience.

And while I have heard some Christians say

that Jesus never judged anyone for their sins,

in studying the gospels, I have found this is not true.

Jesus judged harshly against the sin of self-righteousness.

The idea that I am right, and you are wrong

and because you are wrong,

I don’t need to listen to you, care about you, or seek reconciliation with you.

Among his disciples, Jesus included a tax-collector

who leveraged the government

and exploited the poor for his own profit

and a zealot,

who believed the government needed to be completely overthrown with violence.

He was an expert in forgiveness, humanity, and love.

And this is so often forgotten in our day and age

of hyper partisan politics

and social media platforms.

But when we are more concerned with being right

than we are with forgiveness, humanity, and love,

then, I must ask you

what does our church sound like?

Drip

Drip

Drip

I am not an expert in the matters of war

or in middle eastern politics

I know the Christian church has a long history

of anger, bigotry and violence toward Jews,

and I know the Christian church also has a long history

of anger, bigotry, and violence toward Muslims.

What I do know is this:

Today, April 14, marks 100 days since Hamas

attacked Israel across borders

and, in retaliation, Israel declared war on Hamas.

Since that time over 20,000 people have died from the explosions of bombs

most of them being poor civilians.

No matter who is right,

bombs are not the way of the kingdom of God.

And we have a responsibility

that dates back to the time of Amos

and continued into the age of Martin Luther King Jr.

to speak up and remind the world

of the injustices the rich inflict on the poor.

And if we choose instead to remain silent

for our own convenience

and to keep the peace in our own relationships

then, I must ask you

what does our church sound like?

Drip

Drip

Drip

The spiritual discipline

of service is not for the feint of heart,

the spiritual discipline of service is not convenient,

and the spiritual discipline of service is not handed to us.

But the spiritual discipline of service is the work of God.

And if we are willing to empathize with the poor,

to ask ourselves how we are part of the problem,

to change our behavior for the greater good,

to work against the widening wealth gap in this country,

to rally for the dismantling of bombs

and be less concerned with being right

and more concerned with forgiveness, humanity and love,

then justice will roll down like waters

and righteousness like a mighty stream.

And then, I must ask you

what will our church sound like?